NM Food Drawdown Opportunities

Contents

- 1 Target Categories from Project Drawdown for New Mexico

- 2 NM Top Ten Agricultural Commodities

- 3 General Statistics for the State

- 4 Export Statistics

- 5 New Mexico Agriculture and Food Processing: Future Opportunities

- 6 State Impacts of Agriculture and Food Processing

- 7 Eco-friendly Agriculture

- 8 Edible, Local Crops

- 9 Ranches, Dairy and Livestock

- 10 Ranching Activities in NM

- 11 Land Use Issues

Target Categories from Project Drawdown for New Mexico

Bold items show the most potential. Numbered items and page numbers are cross-references to the solution in Project Drawdown - the book.

- reduced food waste #3 p 42

- plant rich diet #4 p 38

- silvopasture, graze animals in trees and pasture together #9 p 51

- regenerative agriculture, no till, cover crops, no inorganics applies #11 p 54

- conservation agriculture, no till, cover crops but use chemical fertilizer and pesticides #16 p60

- tree intercropping, mix tree crops with other crops #17 p 58

- managed grazing #19 p72

- farmland restoration #23 p 41

- multistrata agroforestry, mix trees, shrubs and field crops #28 p 46

- farmland irrigation (lower in ranking, but important in NM) #67 p 68

NM Top Ten Agricultural Commodities

Farm Flavor reports on NM Agricultural Commodities, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service:

- "New Mexico’s Top 10 Agriculture Commodities" - November 25, 2019

The report is based on cash receipts and excludes statistics for “miscellaneous crops” and “all other animal products.”

1. Dairy Farms Just over 77% of the milk in New Mexico is produced on the eastern side of the state in Curry, Roosevelt, Chaves, Eddy and Lea counties. Milk and dairy products generated $1.3 billion in cash receipts.

2. Cattle and calves Today, about 10,000 families across the state raise beef cattle, and New Mexico lays claim to approximately 387,000 beef cows. Cattle and Calves generated $823.8 million in cash receipts.

3. Pecans New Mexico is second only to Georgia when it comes to pecan production in the U.S., and in 2017, the state’s farmers produced a record-breaking 92 million pounds of pecans. Pecans generated $220.8 million in cash receipts.

4. Hay New Mexico is a major alfalfa hay producer, with 190,000 acres of the crop harvested in 2017. A legume hay, alfalfa is an excellent source of good-quality protein, fiber, vitamins and minerals. Hay generated& $109 million in cash receipts. Conflicting data: alfalfa hay. More than 30 percent of the state’s production is exported. In 2015, the Land of Enchantment produced 893,000 tons of alfalfa hay, with a production value of $188.4 million. The hay itself is used for pasture, silage and greenchop, and it is a significant contribution to the state’s livestock industry, acting as food for cattle and more.

5. Onions New Mexico farmers harvested an estimated 7,100 acres of onions in 2017, and the state is one of the largest summer-onion producers in the nation. Onions generated $106.6 million in cash receipts.

6. Chili Peppers New Mexico’s warm, dry climate and 350 days of sunshine each year make it an ideal place to grow chili peppers. Chile peppers generated $44.6 million in cash recipes.

7. Cotton New Mexico is one of 17 states that produce cotton, and production (in bales) ranks the state 16th. The Land of Enchantment’s upland cotton production is largest in Lea, Doña Ana and Eddy counties. Upland cotton generated $31.9 million cash receipts.

8.Corn New Mexico farmers planted about 125,000 acres of corn and harvested 43,000 acres of corn for grain in 2017, resulting in a production value of more than $22 million. Corn generated $22.4 million in cash receipts.

9. Wheat In 2017, farmers across New Mexico harvested 135,000 acres of wheat. Wheat generated $15.7 million in cash receipts.

10. Sorghum Sorghum is an energy-efficient, drought-tolerant crop, perfect for New Mexico’s climate. New Mexico producers planted 85,000 acres in 2017, yielding 187,000 tons. Sorghum brought in $7.65 million in cash receipts.

General Statistics for the State

In 2015, New Mexico agriculture was valued at a whopping $4 billion, including forest products sold and other farm income, thanks to the 24,700 farms covering 43.2 million acres across the state. New Mexico farms are large with the average size ringing in at 1,749 acres.

The state’s hardworking farmers and ranchers grow and raise important commodities including beef, milk, hay, pecans, corn, wheat, cotton, sorghum, peanuts, potatoes and more (see above). New Mexico continues to be among the nation’s leaders in chili pepper and pecan production, producing 33% and 29% of America’s total production, respectively. Additionally, New Mexico ranks in the top 10 nationally for both cheese and milk production.

Currently, the state has 9,377 Hispanic-operated farms, up from 6,475 five years before. There is also an increase in young farmers, specifically those under the age of 34. The average age of a New Mexican farmer is around 60 years old. Though New Mexico includes conventional farming, organic farming is also a large sector of the agriculture industry, with 116 organic farms recorded in 2014.

SOURCE https://ustr.gov/map/state-benefits/nm

Export Statistics

- "Agriculture in New Mexico depends on Exports"

- New Mexico was the 43rd largest state exporter of goods in 2018.

- In 2018, New Mexico goods exports were $3.7 billion, an increase of 31% ($872 million) from its export level in 2008.

- Goods exports accounted for 3.7% of New Mexico GDP in 2017.

- New Mexico goods exports in 2016 (latest year available) supported an estimated 15 thousand jobs. Nationally, jobs supported by goods exports pay up to an estimated 18% above the national average.

- New Mexico is the country’s 34th largest agricultural exporting state, shipping $762 million in domestic agricultural exports abroad in 2017 (latest data available according to the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture).

Top Agricultural exports (2017 value) were:

| Item | 2017 Value | 2017 State Rank |

|---|---|---|

| tree nuts | $207 million | 3 |

| dairy products | $189 million | 9 |

| other plant products | $91 million | 38 |

| beef and veal | $89 million | 16 |

| vegetables, processed | $38 million | 21 |

Source: "Agriculture’s Contribution to New Mexico’s Economy" - NMSU - December 2014

The combination of agriculture and food processing is an important part of New Mexico’s economy. Together the two broad industries accounted for $10.6 billion (roughly 12.3%) of New Mexico’s $86.5 billion gross state product (GSP) in 2012. In addition, the two industries directly created 32,578 jobs and 18,308 jobs in related support activities for a total of 50,886 jobs statewide.

Agriculture alone accounted for $3.9 billion in sales at the farm/ranch level and an additional $2.1 billion in value-adding processing/distribution, marketing, financing, and supporting services . Agriculture was responsible for a total of 41,961 jobs in New Mexico in 2012, including 26,924 jobs in production-related activities and an additional 15,037 jobs in processing/distribution, marketing, financing, and supporting activities.

Food processing alone accounted for $2.9 billion in products and an additional $1.7 billion in value-adding processing/distribution, marketing, financing, and supporting services. Food processing was responsible for 8,924 jobs in New Mexico in 2012, including 5,654 jobs in production-related activities and an additional 3,270 jobs in processing/distribution, marketing, financing, and supporting activities.

New Mexico Agriculture and Food Processing: Future Opportunities

From NMSU:

When compared to national statistics, New Mexico is below average in processing and utilizing its agricultural output (Ramirez and Crawford, 2005). An overwhelming majority of New Mexico’s agricultural and processed food products find their way to markets outside the state. According to NMDA (2010), 99% of New Mexico’s cattle are sent out of state for processing. Ninety-seven percent of New Mexico’s agricultural products leave the state, but the state in turn imports more than $4 billion in food products annually (NMDA, 2010).

The proximity of many producers to New Mexico’s population centers provides a significant opportunity to increase sales to meet the growing consumer demand for locally produced agricultural products. In 2010, over $13 million in New Mexico agricultural products were sold directly to consumers (via farmers’ markets and other venues). According to NMDA (2010), if New Mexico consumers increased their purchases of food from local farmers and ranchers by 15%, over $375 million in direct farm income would be generated. The total income (direct, indirect, and induced) associated with these added purchases would contribute $725 million per year in outputs and wealth for New Mexico communities (NMDA, 2010).

The benefits of expanded consumer-oriented agriculture and food processing are readily apparent. However, such expansions face a number of substantial hurdles. Not least of these are government policy and private sector investments that will improve the state’s agricultural infrastructure and services. These include financing to implement new technologies to lengthen production seasons and food storage facilities to ensure reliable supplies to wholesale and retail customers. Also needed are improved collaboration, networking, and distribution mechanisms that currently limit opportunities for connecting local producers and consumers to wholesale and retail outlets.

State Impacts of Agriculture and Food Processing

From NMSU:

Agricultural production’s total impact is about 7.4% of New Mexico gross domestic product (GDP). Food processing’s total impact adds another 5.7% to New Mexico’s GDP. According to our IMPLAN analysis, agricultural production ranked 3rd in total statewide impact and food processing ranked 11th in total statewide impact.

For this report, eight regions of the state (each containing from three to six counties) were examined. The total impact of agriculture in each of the eight regions ranged from $224 million to $1.66 billion. In three of the regions, the total impact from agriculture makes it the number one sector in the region. The three regions on the east side of the state accounted for 83% of the state’s total agricultural impact. Agriculture ranked 5th or higher for six of the eight regions, with only two regions (the Northwest and Metro regions) ranked lower than 5th.

Food processing has a higher total value than agricultural production in two of the eight regions (the Southwest and Metro regions). The Metro region, which includes Bernalillo County, is the biggest food processing region in the state. However, even with nearly half of all the state’s food processing, the sector ranks only 25th in importance to the Metro economy. In two regions (East Central and Southwest), food processing is the second most important sector. However, only in the Southwest region is food processing’s impact larger than agricultural production.

| STATE OF NEW MEXICO | DIR. EMPL. IMPACT | TOT. EMPL. IMPACT | OUTPUT DIRECT $ IMPACT | OUTPUT TOTAL $ IMPACT | $ RANK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State & Local Govt. Education | 98,311 | 160,598 | 5,574,507,324 | 9,106,339,439 | |

| Scientific R&D Services | 32,155 | 56,251 | 4,970,488,281 | 8,695,228,758 | |

| AG PRODUCTION | 26,924 | 41,961 | 3,881,871,821 | 6,008,285,299 | |

| State & Local Govt. Non-education | 62,164 | 101,535 | 3,664,326,416 | 5,985,103,474 | |

| Food & Drinking Places | 69,146 | 106,238 | 3,712,477,783 | 5,703,955,481 | |

| Federal Govt. Non-military | 29,545 | 48,746 | 3,288,753,662 | 5,426,083,042 | |

| Construction – New Non-residential | 26,475 | 43,310 | 3,209,204,102 | 5,249,951,667 | |

| Petroleum Refineries | 604 | 665 | 4,326,457,031 | 4,759,017,299 | |

| Banking, Credit Unions | 9,236 | 15,940 | 2,751,842,285 | 4,749,509,082 | |

| Wholesale Businesses | 25,637 | 38,226 | 3,167,260,254 | 4,722,592,393 | |

| FOOD PROCESSING | 5,654 | 8,925 | 2,888,843,602 | 4,635,452,275 |

Regional Analyses are available at NMSU.

Eco-friendly Agriculture

From Dreaming New Mexico

Overview

Although exact numbers are difficult to come by, New Mexico has between 50 to 65 million acres of working landscapes: more than 400,000 acres in field crops for all types of hay and feed grains; about 80,000 in edible crops; and the rest in grazing on private, State, federal and tribal lands. In addition, abandoned range and cropland acres have never been surveyed. To fulfill one long-term dream of food security, the water sources and fertility of the soils of these agricultural lands must be maintained and regenerated. How do you keep up both production and ecological health of land, waters and life that have been hurt by past and present practices?Eco-friendly agriculture, which preserves as much soil, water and biodiversity as possible with as few harmful side-effects as possible, plays a crucial role in long-term food security. There are numerous barriers to eco-friendly agriculture: species hurt by the water diversions and land clearing; dairy and feedlot pollution; predator-management; harms to human health; invasive pathogens, pests, animals and plants. Over 18 species, especially fish and riparian obligates, have been threatened by low flows. Farming has contributed to habitat loss of about 8 endangered plants. The dream for a human and eco-friendly dairy and beef industry is a difficult long-term task. Dairy ammonia and hydrogen sulfide exacerbate eye, nose and throat irritations.In addition, climate change, regulatory pressures, older operators, increasingly diverse operator goals and poorer economic returns have made farm and ranch ecosystem management challenging. The most demanding dream that emerged in DNM’s project was how to compensate ranchers and farmers for eco-services. Ecological services include: carbon- sequestration; regenerating top soil; providing habitat for sensitive species; providing cover/ food/water for wildlife and game (especially wetlands and riparian habitats); increasing pollinators; stopping erosion; reducing harmful floods and invasive species; protecting endangered species; restoring fire regimes; removing toxics from nutrient cycles; and more. Many ranchers and farmers were happy to perform these tasks with some help for labor and equipment. They had no profit motive. Others sought eco-service management as a source of income. The livestock industry has special needs to maintain long-term viability. Livestock industry dreams include ranchers manage herds to co-exist with predators, receiving payment for ecosystem services; confined animal operations (CAFOs) for beef and dairy cows radically limit and remediate their groundwater pollution; livestock nutrition minimizes greenhouse gasses; and CAFOs limit dust and bio-aerosols that cause asthma, and worsen respiratory diseases and allergies. Many citizens dream of a more humane treatment of livestock and fewer bovine growth hormones and antibiotics. Grass-fed and natural beef focus these dreams.

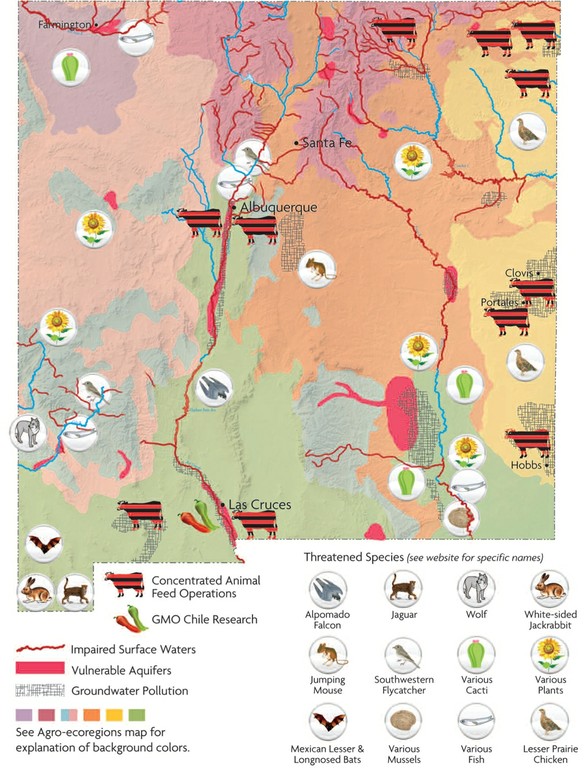

Map

In the dream, farms and ranches are a form of specialized ecosystem management. The map illustrates challenges to agricultural ecosystem management that have harmed the environment: impaired surface water include waters with excess nutrients, herbicides and salinity; vulnerable aquifers are losing their usefulness because water extraction exceeds water replenishment and/or the waters pumped have poor qualities; groundwater pollution comes from seepage of fertilizers and other agro-chemicals into the water table; concentrated animal feeding operations have many issues of public health, environmental pollution (aerosols, wastewater), animal welfare and occupational safety; genetically engineered chiles are opposed by growers of traditional landraces; and threatened species all have conflicts with some aspect of cattle raising, farmland clearing or practices.Each agro-ecoregion has different invasive and sensitive species concerns. The Transition Mountain area of the Gila focuses on wolves and cattle-raising. Each river system has a different species of fish threatened by low flows and different aquatic plants have invaded each river (e.g., the Pecos has been overtaken by the invasive salt cedar). The rangelands all have invasive weeds and grasses that reduce forage values (e.g. Lehmenn’s lovegrass in the arid lowlands).

Edible, Local Crops

From Dreaming New Mexico

Overview

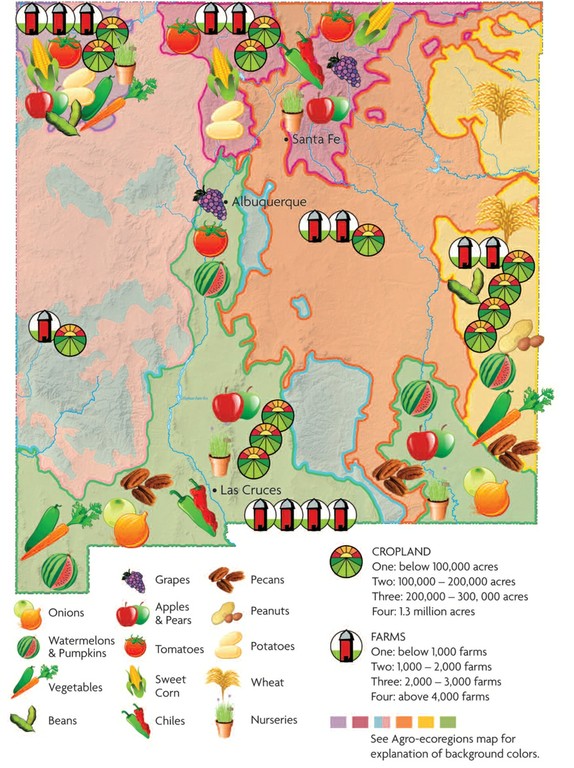

New Mexico has over 5,500 farms that grow directly about 50 edible crops (and endless varieties). Santa Cruz Farms in Española, for instance, grows 76 crop varieties of 3.5 acres. Chispas Farms grows 50 varieties of garlic for sale and over 300 to save the cultivars! The number of both truck market farms and crop varieties planted has continued to grow over the last decade. Top commercial crops for the mass market are: pecans, onions, greenhouse nursery crops, chili (see Boxes) and winter wheat (286,000 acres). Peanuts (about 10,000 acres), potatoes (about 5,500 acres), sweet corn and dry beans (about 7.500 acres) are important in specific agro-ecoregions. There are many farms growing apples (over 900 totaling over 2,000 acres), and over 1,000 acres each of grapes, pistachios, pumpkins, rye and watermelons. Most of the top crops are exported.

Given this mass-market production and local market diversity, New Mexico could eat well (in season) perhaps 50% or more of its edibles from foodshed farms. The exact amount will depend on crop-specific assessments to see what import crops can be most easily substituted and the willingness of farmers to grow the crops.

The typical New Mexico farmer is nearly 60 years old and may not be eager to redesign his or her business. Nevertheless, with good farmland decreasing, an unknown number of these farms and farmers will need to change crops to fulfill the dream.

How can government, private investors and nonprofits help increase farm gate profits and direct edible crops into local markets? A good example was the State Memorial to bring fresh, local foods to schools. The Farm to School program requires farmers to carry a one million dollar insurance policy, to harvest less than 24 hours before delivery, package in three-pound increments, and label each box with the farmer’s name and the package’s destination. Despite this extra insurance and work, this exclusive market segment stabilizes and reduces financial risk to the crop farmer, who knows in advance how much will be bought and at what price. Institutional markets help farmers switch to a new agrarian economy.

Map

Ranches, Dairy and Livestock

From Dreaming New Mexico

Overview

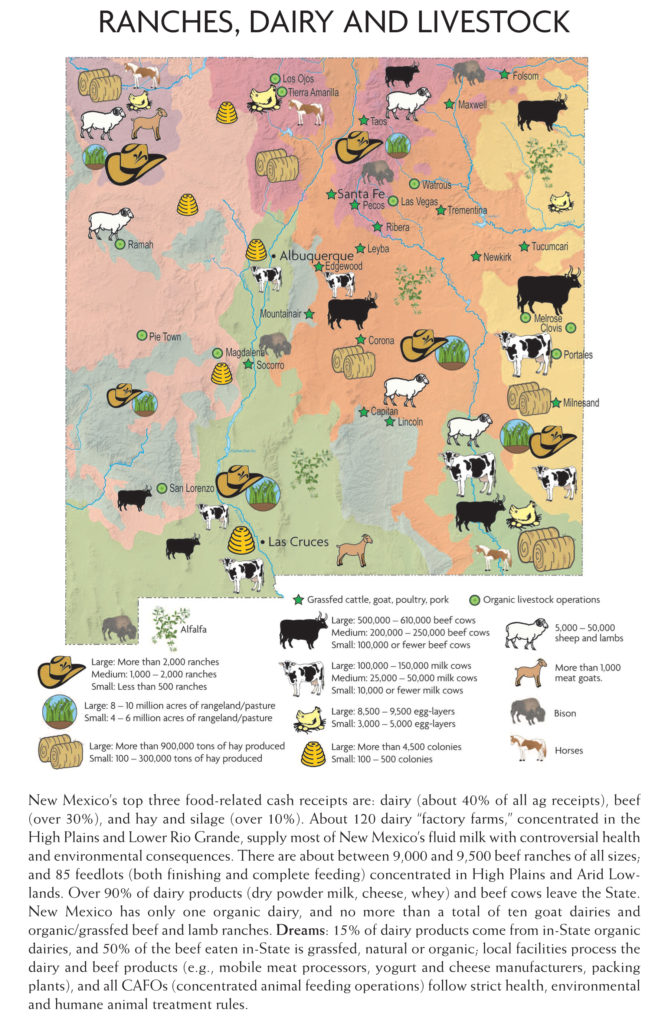

Dairy and dairy products bring the highest food-related cash receipts into New Mexico (40% of all receipts). After dairy, the New Mexico beef industry brings in the highest cash receipts. Beef and dairy depend on New Mexico’s third largest agrarian pursuit — all types of hay, especially alfalfa, corn silage, sorghum, green chop and grain corn.Cattle and dairy raisers participate in three starkly different value chains: local, domestic and export. Creamland Dairies (owned by Dean Foods) produces yogurt, cheese, ice cream, fluid milk, condensed milk, sour cream, whipping cream and other products, selling locally (about $50 million, mostly in New Mexico) and outside the state. Otherwise, the local New Mexico dairy industry barely exists, with only one grass-fed or organic dairy and fewer than ten small organic product manufacturers.Over the next ten years, the dreams of each track of the livestock industry cannot harmonize to “one size fits all.” Europe has recognized this reality for some time and has a two-path value chain — one for the domestic market and one for export. The value chains differ, for instance, in how inspectors track beef cattle from production through slaughter, packing and distribution. They have different rules (performance standards) because international trade has a greater risk of spreading diseases like Mad cow or foot-and-mouth. Export demands require different shipping conditions. When tri-track rules for local, domestic and export are well designed, they can spur within-chain innovation, investment and efficiencies that cannot be achieved with a single set of health, ID tracking, slaughtering and processing rules.The barrier to local scale up has allegedly been cost, though some Midwest studies indicate that given equal access to government payments, small dairies can compete with CAFOs. The commodity milk industry benefits from federal Milk Marketing orders (a price support program), direct payments to producers, and the Dairy Export incentive program (essentially a subsidy for nonfat dry milk, butterfat and certain cheeses).

The most accessible market niche is “New Mexico 100% grass-finished beef.” The cattle are “matured on grass” which means the minimum number of grazing days must be at least 120 days with each agro-ecoregion’s “personality” making the grazing season’s dates variable. (Over-wintering can be a difficulty for grass-fed cow-calf operations.) Though not strictly organic and with occasional problems of tenderness and taste, grass-finished beef is drug-free, grown from local cattle and has higher nutrient values.

Map

Ranching Activities in NM

From NetState

Livestock

Dairy and cattle ranching are the most important agricultural activities in New Mexico. About 39% of the state's total agricultural receipts are generated by dairy products. About 37% by beef cattle and calves. Beef cattle are shipped to other states for fattening and slaughter. Sheep and lambs and hogs are also important.

Crops

Water is scarce in New Mexico and most croplands must be irrigated. Not surprisingly, the leading crop is hay used to feed cattle. Pecans rank second behind hay and account for about 3 or 4% of the state's total agricultural receipts. Greenhouse and nursery products generate about 2% of New Mexico's total cash receipts. Other crops are grown as well and New Mexico is a leading producer of chili peppers and onions. Some cotton, grain sorghum and wheat is also grown in the state.

Land Use Issues

NPR reported:

- Like in much of the Southwest, vast tracts of range land here are owned by the federal government. Many ranchers depend heavily on their federal grazing allotments, which tend to be passed down through generations.

- "You do own something, you know," Kelly says. "We don't own the dirt, but we do own the water rights and the forage rights and you pay for that."

- Ranchers pay modest permit fees to graze livestock on federal land. But most, like the Goss Family, have tens of thousands of dollars — and decades of use — tied up in their business and infrastructure out here.

BLM Grazing Fees Announcements